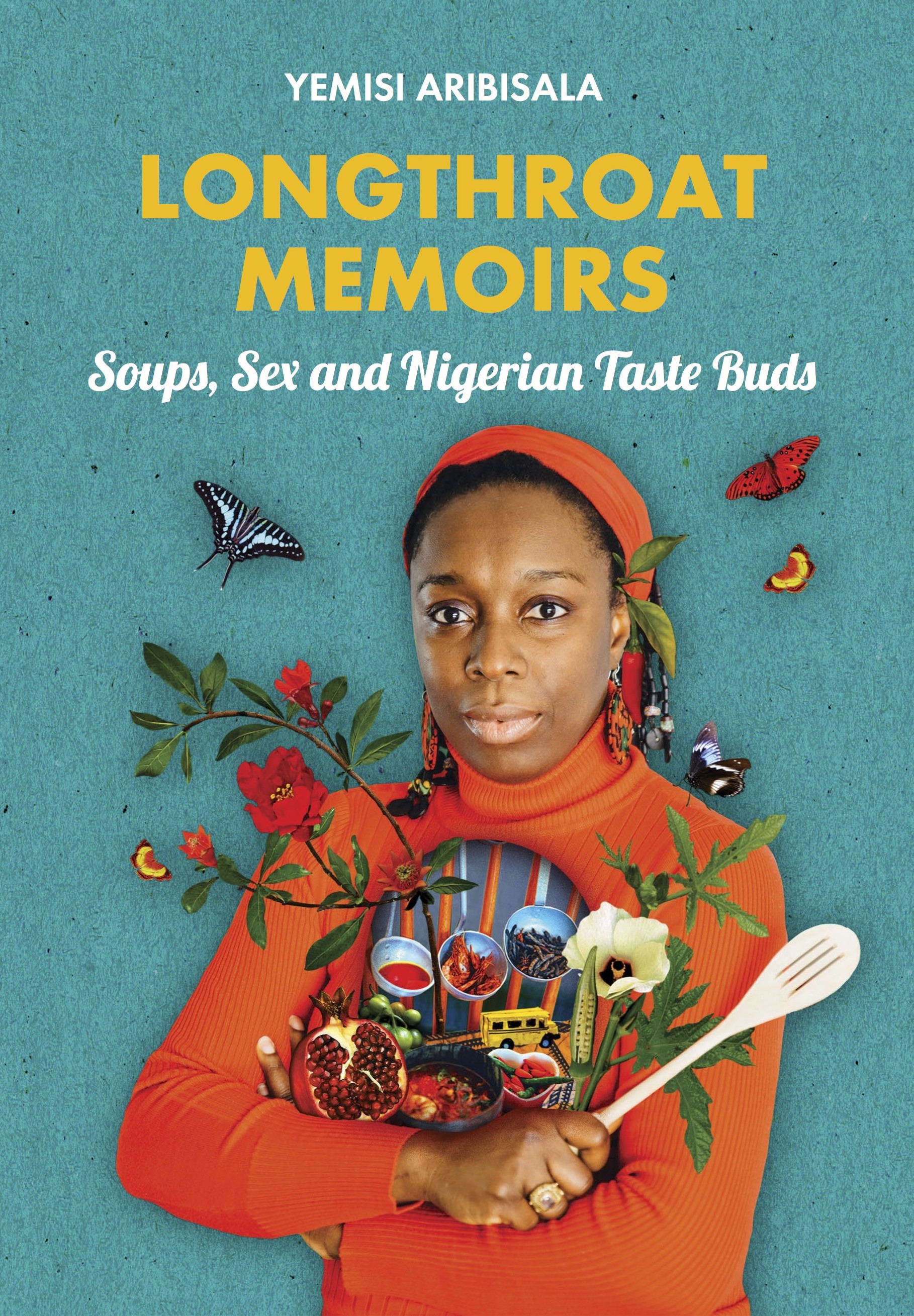

This is about Yemisi Aribisala and her brilliant book – Longthroat Memoirs: Soups, Sex and Nigerian Taste Buds which I’ve thoroughly enjoyed reading. I’ve also had the great pleasure of asking Yemisi some questions – which she graciously answers.

I first ‘met’ Yemisi in 2010, 2011 – online, in the words she penned in FOOD MATTERS on 234NEXT. Miles apart, I found kith and kin. She wrote beautifully, not just about food, but about culture and ingredients, about place and places, about discovery. Away from home, her writing comforted me in a way that only food can with its shared memory and experience.

In 2011, I moved back home to Nigeria. Desperate to find out the name of a fruit which I now know as Epapa, I hunted her contact details – we have mutual friends from my days (unknown to me then) in Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife (1993 – 1997). We might have crossed paths as she was there from ’89 to ’93, an unconscious, unknown baton-changing, who knows :)? And then we spoke about a project I wanted to start. It was then she first mentioned her book, writing it.

In 2012, when I went a cherry-plucking and read about Yemisi’s escapades with pitanga, I smiled. Kinship. Recognition. Some sort of ‘ship. Foodship, friendship, ‘ship ‘ship.

Her book, in 2016 is a relevant discourse, and discussion on Nigerian cuisine – poorly understood, often misunderstood, spoken very little about yet necessary to the sustenance and survival of our cuisine. I’m super excited – and motivated too.

Hope you enjoy the Q & A. Let me know what you think and yes, below, there are links to where you can get a copy.

—–00000—–

How long did it take you to write Longthroat Memoirs? Did you feel like you would never finish? What gave you the push?

It took me a few hours to consent to writing on food – to think of a response to a phone call from an old colleague Ebun Feludu and from Jeremy Weate, co-founder of Cassava Republic Press. They called me from 234Next, the Newspaper. For two and a half years after that I was preoccupied with getting out the blog, called Food Matters every week. On some weeks I broke my promise to write because I was pregnant or and dealing with two small children, running a business from home, and life was usually doing something unpredictable. When I did realise and commit to the full throes of writing a book on Nigerian food a collection of the Food Matters blogs– that is when Bibi Bakare Yusuf and me were in the excruciating process of looking over each article and deciding its true potential beyond the limitations of newspaper word counts and attempting to build a firm readership for a subject-matter that people were still not sure was worth discussing-yes I felt like I was facing something insurmountable. And yes I was afraid terminal heartbreak was round the corner. Dr. Bakare Yusuf has very high standards for work, far and above my own perfectionist standards. Her standards are terrifying in fact. I was discouraged by the revolving load of editing and re-editing that needed to be done. The first set of edits I couldn’t even look at for close to a year because my confidence was crushed by the proliferation of red lines and suggestions, and requests to clarify what I was saying – around every line and comma of my writing.

The push – the one that finally brought the baby was (believe it or not) the disbelief of my family. They gave up – they had been waiting many years for “the book” or the glory or the money, anything really, to justify this hobby I’d been preoccupied with for so long…and there was no sign of any of these wonderful visitors. I was often asked if I was being paid for all the articles I was churning out – I wasn’t. I knew I couldn’t pamper myself and the book just had to be finished. In 2013 out of desperation for space in my head and in my heart and in the rooms about me in which to finish the book, I spent all my savings to pay for a flat in Lekki Phase 1. It was work-space but we lived in it too. The best part by far was disappointing all the endings that had been imagined and expressed for me and my everlastingly worked-on Nigerian food-book. How long did it take me to write the book –8 years going on 2 decades.

[‘Oh my word!’, Ozoz says]

Why Longthroat Memoirs for a name? I know what Longthroat means but…?

Longthroat Memoirs is the title of a chapter in the book that is deliberately crammed full of nostalgia. As a child I spent my long holiday months at my grandparents’ home in Oke-Ado, Ibadan. I loved the house for many different reasons. Best of all because I was left alone to read books that were in an upstairs room for as many hours in the day as I liked. There were two balconies in the house – one in front and one at the back with a view of the Ijebu-bye pass. The former had a view of the street the house sat on and food hawkers that carried everything from moin-moin made with palm oil to fresh meat past the house, and up and down the street.

Longthroat Memoirs is the title of a chapter in the book that is deliberately crammed full of nostalgia…

the chapter struck me as representing everything about the book – a collection of words that send signals to the brain and create sensations, love, nostalgia, hunger. The food isn’t in front of you, but you are forced to engage an image of it and respond to it.

If someone is or has longthroat, then there is no end to their appetite or the length or depth of their gullet.

I think I have officially earned my appropriation of it by writing a whole book on Nigerian food and appetite and stories…and loving food just by the way.

They all had a distinct call so that you didn’t have to look to know who was passing. My siblings and me were fascinated endlessly – no matter how many times these hawkers went past the house calling out. We weren’t allowed to go downstairs and stop them and buy anything but the inability to do that made imagining what was being sold even more vivid. Words related to food being called out “moin moin elepo” when they entered your brain sent off all kinds of signals-olfactory ones, visual ones, even your salivary glands began to work overtime. You imagined the texture and aroma of the moin-moin. When I finally had to decide for a name the chapter struck me as representing everything about the book – a collection of words that send signals to the brain and create sensations, love, nostalgia, hunger. The food isn’t in front of you, but you are forced to engage an image of it and respond to it.

The word longthroat is understood by every single Nigerian, and I knew it was a great flag to hold up to create the expectation of a story. One that has to do with the belly. I put myself outside our context and saw the word “longthroat” for the clever thing it is. If someone is or has longthroat, then there is no end to their appetite or the length or depth of their gullet. I didn’t want anyone to run ahead of me and claim the word. I just had to own it. I think I have officially earned my appropriation of it by writing a whole book on Nigerian food and appetite and stories…and loving food just by the way.

What did you discover about yourself as you wrote? About your relationship with food, Nigerian cuisine in particular and culture?

I discovered that like a lot of my generation living in urban spaces, I was claiming to be Nigerian but was not an expert on anything Nigerian. Even the Yoruba I spoke had a half-heartedness to its use. I didn’t want to be a visitor in my own life and context, in my country, and food turned out an enjoyable way to dig deep into knowledge about where I lived, who I was, what people did before I got here. As I researched and wrote I found that I didn’t really understand the food that I was handling and eating, not really, nor the reasoning behind it, so I started to ask questions and visit people’s kitchens to learn. These people were all in the generations before mine and unlike me in mine, they had higher standards for their citizenship of the country they claimed. They understood the proverbs in every day speaking. There was no pretentiousness to their love or ownership of our food, or their wearing of clothes, or their commitment to who they were.

So researching Nigerian food, talking about it, helped me determine in concrete terms who I am. There is also an added dimension to the relationships I have with my children that cooking provides. Around the table with my children they have other terms of references for communicating with me and vice versa. They know I’ve written a book on Nigerian food and that achievement encourages them to think deeply on what goes into their mouths and into their lives generally.

I found lost pride and secrets hidden in Nigerian languages in thinking and talking about food -For example when I found out in making notes for the chapter called Stolen Waters, that people grow corn in silence because bad words destroy the harvest, it made instinctual sense. We water everything with words, our lives, our children, our happiness. I found that all the secrets of food inform and nourish all the issues of life. Longthroat Memoirs Soups Sex and Nigerian Tastebuds was my way of owning my Nigerian citizenship – not by whining nor by negativity but by gratifying stories about Nigeria and Nigerians.

Are you a hoarder or a minimalist? How did that influence your writing style?

For sure I am a hoarder. My house is full of old books, second hand rugs and salvaged tree trunks. I have letters my grandparents wrote to me in the early 2000s-newspaper clippings and magazines from the 1990s. Recently, I drove past a pine being cut down in Heritage Park near where we live and begged for part of the belly of the tree. It is now a book table. Having a problem with throwing things away is apparent from reading Longthroat Memoirs.

As Marta Maretich says in her blog post on Longthroat Memoirs, Soups, Sex and Nigerian Tastebuds – the book is a wild ride and an incantation. You can hear lots of collected stuff moving around in the two definitions. The book could easily have been bigger. The Chimurenga Chronic who normally publish my work will tell you I have a problem with word limits and tangential discussions. It’s the style of someone who has to keep tabs on lots of hoarded stuff.

Knowing what you do now, what would you do differently if you had to do it all again, write this book all over again?

I would get on with it (In the words of Jeremy Bovenga Weate). Get on with the writing of the book. I would go to a market where they sell confidence and buy a big bag of it and just get on with it. [Ozoz says THANK YOU]

What’s your favourite recipe to cook and eat ever?

I don’t have a favourite recipe. I’m very much a person that eats by mood and colour and hormonal ups and downs. Certain times of the month all I want for days on end is cheese – just great big slabs of Brie. If I wouldn’t put on weight, I could eat a gigantic wedge a day. Red food pulls me from across the room and I find myself eating strawberries because they are so beautiful and red, not because I really want to be eating so many of them. Worst of all chocolate.

The dish in my mind though if I am thinking comfort food would have to be yam pottage made from old yam with palm oil, soft ripe plantains, onions-a sprinkling of Afang at the end of cooking, a bit of burning underneath, everything cooked in a local earthenware pot.

Are you one of those people who can’t eat their own cooking, immediately the soup is done?

Out of necessity – because of food intolerances, I must eat my own food. I can count the number of times I sit down to a restaurant meal in a year. The last time I ate in one was last year. I quite like my own food especially because I can have it just they way I want it.

—–00000—–

Thank you, Yemisi – for sharing you and your wealth of knowledge of Nigerian cuisine with me, us, the world. So much inspiration. Peace, love and more stories.

You can find Longthroat Memoirs: Soups, Sex and Nigerian Taste Buds, to buy here:

Leave a Reply