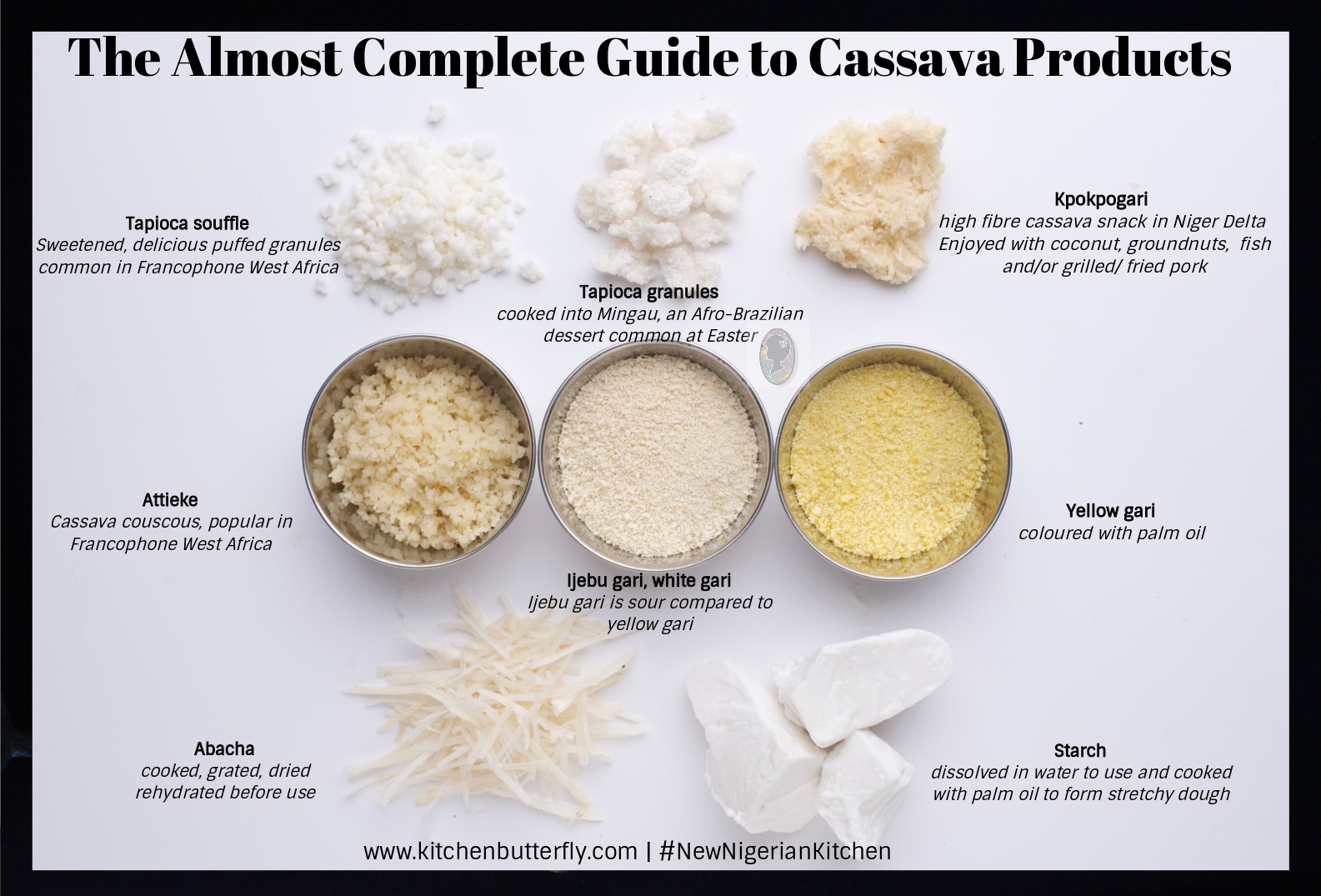

It is difficult to think of cassava as a recent import to Nigeria (and Africa) because much of its cuisine today is based on the tuber in different forms. From snacks of boiled cassava with coconut – popular street food; kpokpogari – coarse, hard biscuits of cassava fibre from which all the starch has been pressed, ‘soaked gari’ – a fine to coarse meal soaked as cereal with water or milk; to sides like ‘eba’, hot sticky dough similar to mashed potatoes but starchier and served with soups and stews; to salads of abacha, made from re-hydrated, shredded cassava; and desserts of mingau, made with tapioca granules and coconut milk; cassava and cassava products are essential to life and daily living for majority of Nigerians, across all spheres of society.

By recent, I speak relatively. The crop – not native to Nigeria was first introduced to West Africa by Portuguese explorers and slave traders somewhere in the 16th century. However, it didn’t take root till the late 19th century, possibly because methods of processing – some varieties are toxic if not processed correctly – were not well known. Circa 1888 when slave trade was abolished in Brazil (the last country to do so), enslaved Nigerians returned home, bringing with them knowledge and techniques of processing it thus expanding its uses. In addition, colonial powers encouraged and supported its cultivation for its hardy nature: resistant to locust attack and sustained growth even where water was a challenge.

——

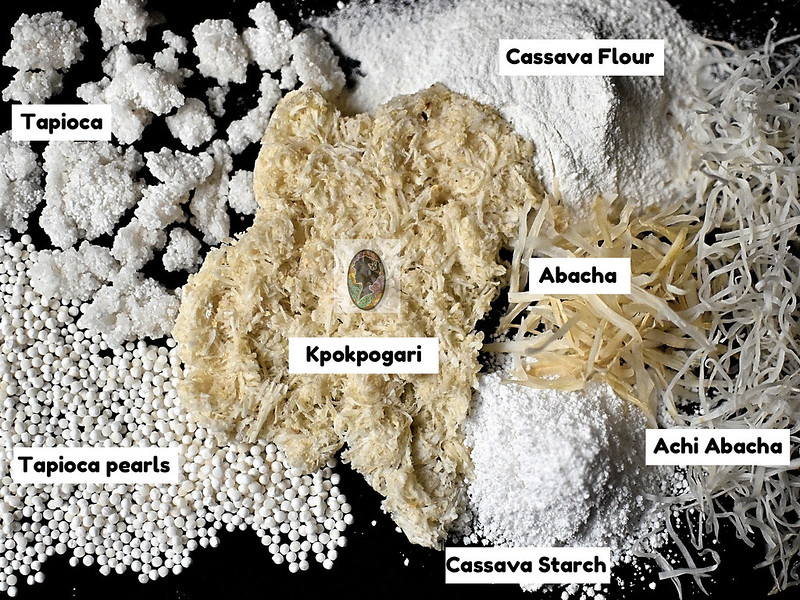

Cassava is processed into various forms, most soaked and fermented prior to use so it is edible – toxicity reduced and its products are shelf-stable.

These are different cassava products – some made from the whole, peeled tuber and others, extracted starch from the cassava.

Cassava flour

Other names: Akpu Nkpo, Igbo; Lafun, Yoruba; Flawan Rogo, Hausa

Cassava tubers are peeled, cut into pieces and soaked for seven to eight days. During the soak, they soften and rid the tubers of dangerous hydrocyanic acid. After soaking, the tubers are sun dried till moisture free, about three or four days after which they are milled into fine flour. To cook, the flour is added to boiling water and stirred continuously till a stiff dough is formed.

Fufu

Other names Akpu, Igbo; Loi Loi; Santana; Mr White; Six-to-six

To make fufu, cassava tubers are peeled, cut into pieces and soaked in water, like for lafun. After 3 to 4 days, the soft cassava is mashed. Lumps, fibres and other stringy bits are removed. The result is further processed by sieving to remove all lumps. The ‘smooth’ cassava mash goes in a sack, ‘is weighted down and the cassava ‘whey’ allowed to drain. The result is a spongy dough which is then cooked – like lafun to create fufu.

Fufu is known for it’s fermented aroma and sour taste as well as being super filling – hence the ‘six-to-six’ name.

Attiéké

Attiéké is similar to couscous which is milled from durum wheat. It is common in Francophone West Africa. In fact, attiéké is to Francophone West Africa what garri is to Anglophone West Africa – a staple, a regular.

To make attiéké, cassava tuber are peeled, cut into pieces, washed and grated. Once grated, the cassava is mixed with a starter culture, magnan extracted from three day old boiled cassava tubers. The mixture is left to ferment overnight, covered after which the resulting dough is placed in a bag and weighted to dehydrate. The ‘cake’ is then passed through a sieve to produce partly dried couscousesque grains which are then steamed and sold fresh.

Gari, Garri

Gari comes in various grades of milled cassava with fine to coarse textures and flavour differences based on length of fermentation and the addition or not of palm oil which changes the colour.

To make gari, one essentially follows a similar process as for attiéké. Peel, wash, grate, ferment for two to three days. Lets pause here for a minute to talk about taste and length of fermentation. The longer the fermentation, the more sour the result and the less starchy the gari. Once this stage is concluded, the next steps are pressing and sieving the gari. Now instead of steaming for attiéké, it is fried in a dry pan. Another differentiator beyond the taste is the addition or not of palm oil. Without it, your gari is a creamy-white meal.

With palm oil, anywhere from a light corn silk yellow (?) to a not-quite-sunny bright one.

Garri is interesting and reacts differently in water, depending on the temperature. It can be eaten cold, like cereal. Water features as the primary vehicle. Sometimes, people go the proper cereal route by adding milk but that’s up to the ‘soaker’. In cold water, the gari grains generally stay discrete. Both colours/ types can be soaked or cooked.

In hot water? Different ball game. The starch gelatinizes such that in hot water, a sticky dough is made. This is popularly known as eba.

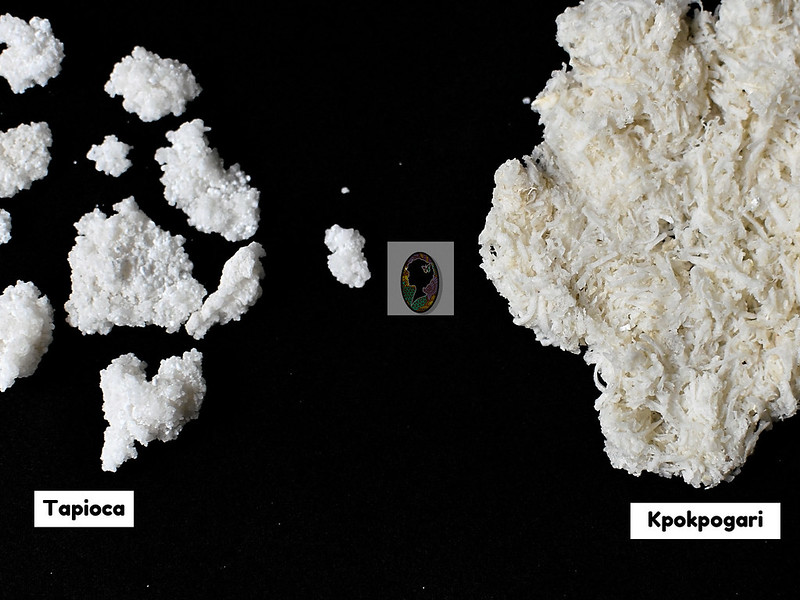

Kpokpogari

The process for making kpokpogari is similar to that for gari – the blended pulp is put in bags and left to drain for days. Unlike gari, the cassava mix is not sieved before frying. Instead, it is commonly salted and then fried with lumps, fibre, everything. The result is a hard, rough cassava biscuit-cake. It is one of the cassava products with high nutritive values because it hasn’t been stripped of the fibre/ roughage.

It is also resembles what the Yorubas and Afro Brazilians call Tapioca, used to make a dessert of mingau, popular at Easter time.

Tapioca

The name Tapioca is derived from the Tupí word tipi’óka, a name in the Tupí language spoken by natives when the Portuguese first arrived in the North-East Region of Brazil around 1707. Tupí refers to the process by which the cassava starch is made edible.

To make tapioca – granules and pearls – the cassava is peeled, then finely grated or milled. This is washed and the fibrous pulp removed, leaving the starchy cassava water or whey. This water is left to settle for a about 6 hours after which the water is decanted leaving a thick, starchy slurry. This is then dried or baked at low temperatures – pieces raked, broken up into bits.

Tapioca Pearls

Tapioca pearls are rolled, pre-cooked/ moist cassava starch passed through a sieve under pressure to produce a pearl-like appearance. To get tapioca pearls, a dough is made from tapioca starch and hot water.

Abacha

For Abacha, cassava tubers are peeled, boiled, shredded/grated on a special grater and then soaked in water overnight. The following day, the shreds are rinsed and drained before being sun-dried.

The shreds are re-hydrated – in cold water for best results as hot water causes the starches to gelatinize – and then used.

It also gives its name to a dish of rehydrated cassava shreds tossed in a palm oil emulsion and finished with chopped garden eggs and herbs.

There are at least two types of Abacha – a more common one featuring somewhat straight shreds, about 1/3 – 1/2 a centimetre, off-white in colour and a less common one – Achi Abacha, whiter, thinner and curlier shreds. Both are used in the same way.

Mbrakasi

Bobozi, Bobozee, Bini?; Akpu miri, Aki beke, Jaakwu Nmiri, Mpataka, Igbo; Air Condition

Cassava tubers are peeled, washed and cut into chunks which are later sliced into ‘chips’. The chunks are then boiled till cooked through. They are left to cool and then cut into chips, along the length, the grain. The chips are soaked overnight in cold water. Some varieties turn slimy and have to be rinsed several times the following day, after the soak. The rinse gets rid of both the slime and the sour, fermented taste developed from the overnight soak.

Nigerian Cassava starch

Cassava starch is produced from the wet milling of fresh cassava roots. Cassava tubers are peeled, washed, grated / rasped/ shredded then mixed with water from which the starch is extracted. The next steps involves starch washing and sedimentation – the mixture is left to settle, with the thick starch slurry settling out. The water is decanted and the resulting starch is sold wet – in blocks, or dried – after granulating, milling and drying.

It is cooked with a touch of palm oil which renders the result a bright sunny yellow colour.

Brazilian Cassava Starch

Brazilian cassava starch, known as fecula de mandioc is a powdered version of cassava starch. It comes in two varieties – sour (azedo), fermented before processing; and sweet (doce). In Brazil, it is used to make crepes in a special process of moistening the flour, sieving and pan-cooking. The wet cassava starch, dissolves in pan and comes together to create crepes which are then filled.

Cassava souffle

Puffed cassava – delicious, delicious, delicious. I tried this in Cotonou and fell in love. The process must be similar to that for tapioca. However, the grains are often lightly sweetened prior to being sold/

——

So there, a few cassava products. Did I say a few? Oh well, we’re open to learning more so share.

I’m also going to look at a few novel cassava products from around the world. Soon.

Leave a Reply