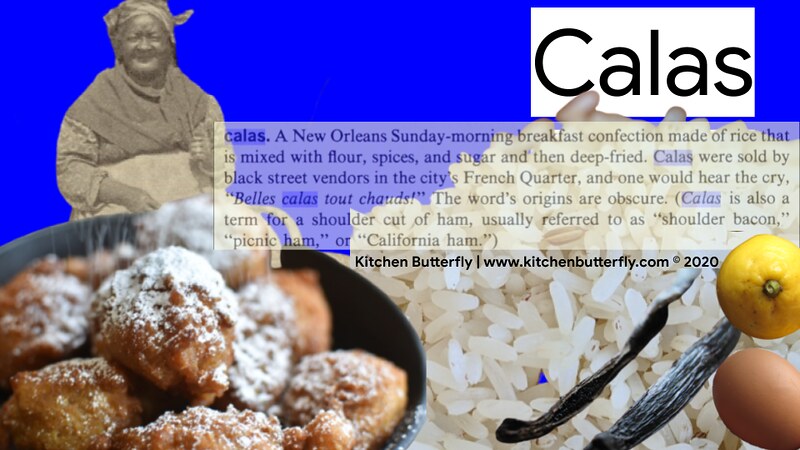

The history of Calas, rice fritters is linked to enslaved West African women. The word itself sounds like a contraction of Akara – so ‘Kara/ Kala/ Cala.

The Dictionary of American Food and Drink (click borrow at the top to view the entry) calls them a New Orleans breakfast sold by black (note enslaved) street vendors but describes the origins as ‘obscure’. It also includes a recipe.

‘Obscure’ meaning uncertain but I’m certain this legacy of Calas is rooted in West African history. First, the name and its likely connection to Akara – a food of the enslaved in Brazil.

I find this ambivalence irritating, this flossy, fragile language used often in historical texts which involve black/ enslaved West African histories, as though reluctant to give credit where due, a sluggishness to credit enslaved West Africans with culinary knowledge and excellence.

One of the first spaces of freedom for enslaved people of West African heritage in the countries they were enslaved in was the streets. Many women – from selling street food – procured their freedom and those of family members.

In an article, ‘Baianas of the Acarajé: A Story of Resistance’, Carolina Cantarino writes: ‘The trade of acarajé had its beginning back in the years of slavery when the so-called earning slave women (escravas de ganho) who worked on the streets for their mistresses (usually small impoverished owners), carried out several activities, among them, selling delicacies on their trays. Back on the East (- should be) West Coast of Africa, the women already carried out the itinerant trade of edible products, which gave them some autonomy in relation to men and many times the role of family provider.

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library.

The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1834 – 1839.

The street trade in Brazilian cities enabled slave women to raise their condition above that of merely servicing their masters: they guaranteed, on several occasions, the subsistence of their own families, they were important for the establishment of community bonds among urban slaves and also for the creation of the religious sisterhoods and the Candomblé. Many daughters of saints started to sell the acarajé in order to fulfill their religious obligations, which had to be renewed periodically.’

In addition, street selling was well established in West African society long before enslavement and continues till this day without question.

Records from the early 19th-century show street selling, common from Bahia to Rio de Janeiro.

In March 1878, Emília Soares do Patrocinio and other food vendors published a petition in the Brazilian newspaper Jornal do Commercio opposing the exorbitant increase in rents at the local market.1 For decades, Emília had been selling vegetables and poultry at many different stands at the port market (Mercado da Candelária), and, by doing so, had become relatively wealthy.2 When she died in 1885 she bequeathed three houses, twenty slaves, jewellery, and money to her heirs.3 It was a remarkable career for a West African woman shipped to Brazil in the first half of the nineteenth century and who had spent a great part of her life in slavery before buying her freedom in 1839. Emília Soares had hired a stand at the market, which meant a move to formalized areas of food selling. It required capital and was the mark of a relatively high social position for a woman like her. The case of Emília’s upward mobility is indeed remarkable in its rarity, since most of the Quitandeiras had only a stand at the beach or worked as small ambulant traders under precarious living conditions. African women involved in the street-food sector were called Quitandeiras. At this point it is helpful to take a linguistic sidestep to clarify the origin of the word. Quitanda is a loan word adopted from Kimbundu, the second largest Bantu language, and means “to sell”.4

Street Food, Urban Space, and Gender: Working on the Streets of Nineteenth-Century Rio de Janeiro; MELINA TEUBNER, Universität zu Köln, a.r.t.e.s. Graduate School for the Humanities, Albertus-Magnus-Platz, Cologne, Germany; IRSH 64 (2019), pp. 229-254 doi:10.1017/S0020859019000130

© 2019 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis

In 1933, Gilberto Freyre, a Brazilian sociologist published a book ‘Casa Grande e Senzala (original, Portuguese) to English, The Masters and The Slaves which explores the creation and framework of Brazilian society.

In it, he shares a lot of the activities of enslaved people – particularly women and street food – from their prized culinary skills to the deftness they showed in creating a variety of delicious foods. In it, he also makes reference to several things that support the links between Akara, Cara, Calas, Rice and street food.

There was a lot of movement between America and Brazil during the times of enslavement and records of movements of the enslaved between both countries show the vast possibilities for these ideas, the recipes of Afro-Brazilian ‘Cara turned American South Calas.

So, now that my soul is soothed some with these notes, here’s my recipe for Calas, adapted from The Dictionary of American Food and Drink.

These are a delight.

- One – they use leftover rice

- Two – they are super easy to whip up

- Three – they fry so well, so easy – they don’t fall apart in the oil, they hold, every fear conquered.

I thoroughly enjoyed making them and retracing edible steps down roads of etymology and place, about street food in enslaved spaces and about the beauty that remains, in spite of.

Ingredients

- 2 large eggs

- 1/2 cup granulated white sugar

- 1 teaspoon vanilla extract

- 1/4 teaspoon cinnamon powder

- 1/4 teaspoon ground ginger

- 1/4 teaspoon ground cardamom

- 1/4 teaspoon ground cloves

- 1/4 teaspoon ground nutmeg

- 1/2 teaspoon salt

- 2 cups cooked rice (cooled) – I used Nigerian Abakaliki rice

- 1 1/2 cups all-purpose flour, sifted

- 2 teaspoons baking powder, sifted

- Vegetable oil for deep frying

- 1/4 cup confectioners’ sugar

Directions

Make Calas batter

In a large bowl, whisk the eggs

Add the sugar, vanilla extract, lemon zest, spices and salt

Stir in the rice and ‘whisk’ or mix well with a wooden spoon

Sift in (yes, again 🙂 – these will lighten your fritters) your flour and baking powder then fold in with a spatula – the result of mine looked like thick/ cold rice pudding.

Fry Calas

Heat up some at least 3 – 4 inches of oil in a deep pot

Set your oil on medium heat while the batter rests, 5 – 10 minutes. I’m a big fan of letting ALL batters – without exception (at least not yet) rest

Once the oil is hot (about 365 F) – you can test with a tiny bit of the batter – it will sink but should rise in 10 seconds or less

Using two spoons – grease both by dipping in the hot oil. It’ll ease the journey of the batter from spoon to fry town

Fry in small batches – I did 6 at a time in my small pot

Let them cook for 6 – 7 minutes, or more on both sides till golden. Cooking on medium heat for me means that they cook through without absorbing oil – perfection

Once they are gorgeous and golden, remove from the oil with a slotted spoon onto a plate or platter lined with kitchen tissue

And now, it’s time for the final crown – sieve some confectioners sugar onto them and let it rain, rain joy

And here’s what they look like inside – speckled, some rice grains still visible, held together by the lightest, most lemony, most warming spices batter that maps a web around rice and sweet and delivers such yumminess in every bite.

Every bite from the crunch, mottled exterior that reminds me of puffpuff and buns at the same time to the fragrance of lemon, the sweetness, the texture of the rice that’s rice and not, all at the same time.

Have you tried calas before? Share all.

Leave a Reply