First published in 2019.

Intro photo changed in 2023 to update the name of Amolili (Nigerian Date Syrup) to Amoriri (Nigerian Black Plum Syrup)

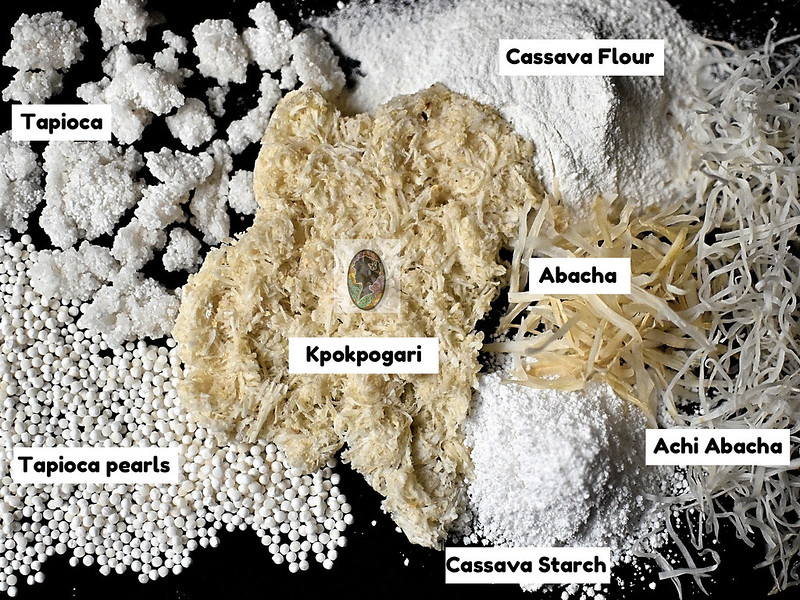

It’s difficult to think of cassava as a recent import to Nigeria because much of its classic cuisine is based on the tuber in different forms. From snacks of boiled cassava with coconut – popular street food; kpokpogari – coarse, hard biscuits of cassava fibre from which all the starch has been pressed, ‘soaked gari’ – a fine to coarse meal soaked as cereal with milk; to sides like ‘eba’, hot sticky dough similar to mashed potatoes but starchier and served with soups and stews; to salads of abacha, made from rehydrated, shredded cassava; and desserts of mingau, made with tapioca granules and coconut milk; cassava and cassava products are essential to life and daily living for majority of Nigerians, across all spheres of society.

By recent, I speak relatively. The crop – not native to Nigeria was first introduced to West Africa by Portuguese explorers and slave traders around the 16th century. However, it didn’t take root till the late 19th century, possibly because methods of processing – some varieties are toxic if not processed correctly – were not well known. Circa 1888 when slave trade was abolished in Brazil (the last country to do so), enslaved Nigerians returned home, bringing with them knowledge and techniques of processing it thus expanding its uses. In addition, colonial powers encouraged and supported its cultivation for its hardy nature: resistant to locust attack and growth in limited water supply.

Nigeria is not a country where desserts are regular. Things are changing, yes… but for many years, fresh fruit salads, cake and ice cream, ice cream and jelly were the staple third course when they featured, and that was often at parties and celebrations of sorts. The exception? Desserts of Afro-Brazilian heritage brought back to Isale Eko, Lagos Island by Christian Brazilian returnees at the turn of the 19th century from Bahia, northeastern Brazil.

In an article, Stronghold of Yoruba Culture, E.L Lasebikan writes in Black World/ Negro Digest (December 1962), ‘….and the words, ‘feijao,’ ‘farofa,’ ‘mingau,’ ‘arroz doce,’ ‘canjica’ which travelled back to Lagos with the return of the Brazilians (of Salvador) towards the end of the last century with little or no orthographic change have become household words among the ‘Aguda’ of ‘Popo Aguda’, that is the Brazilians of Catholic Mission Street, Igbosere Road, Campos Square, and the environment, sometimes referred to as the Brazilian Quarters.’

Mingau de tapioca has assumed prominence and pride of place across the waters, feasted on once a year at Easter – a period of Christian rebirth and renewal – of transformation, triumphant entry and victory over evil.

In Salvador, sweet and savoury foods play a key role in honouring the gods, accompanied by song, dance and ritual feasting. Mingau de tapioca is commonly eaten during the Festa (festival) of Iemanja in early February. Though popular for breakfast, it is notably consumed around this time.

————-

Many of these dishes feature coconut in some form or the other – from its milk in feijao (of beans, called frejon in Nigeria), mingau (with tapioca), canjica (with cornstarch); to grated flesh in cookies like beju, combined with gari. At first, I wondered why and how.

It turns out that the coconut, fruit of the palm cocos nucifera was brought to the West Coast of Africa – like cassava – by the Portuguese who first, discovered and transported an Indian Ocean variety to the New World. From the New World, the coconut took root in West Africa from where it was ‘exported’ to the Atlantic Brazilian coast and the Caribbean, thriving where planted along the way and in plantations where they tended to be intercropped with cassava.

It is no surprise that they – cassava and coconut – are also paired on the plate, in various forms.

‘Eating is an Agricultural Act; Wendell Berry’

————

I’ve been fascinated by mingau since the first time I saw granules of Tapioca trapped in a glass box at a Lagos Island store, many moons ago. Intrigued, I asked a store attendant what it was and she said ‘Tapioca, for mingau’. It would take me some time but I would learn that mingau was similar in some ways to tapioca pudding sans the eggs.

While tapioca pearls are made from cassava starch, that for mingau is made of granulated cassava, processed to rid the toxic tuber of cyanide compounds and milled into granules of varying sizes, from milli- to centimetric.

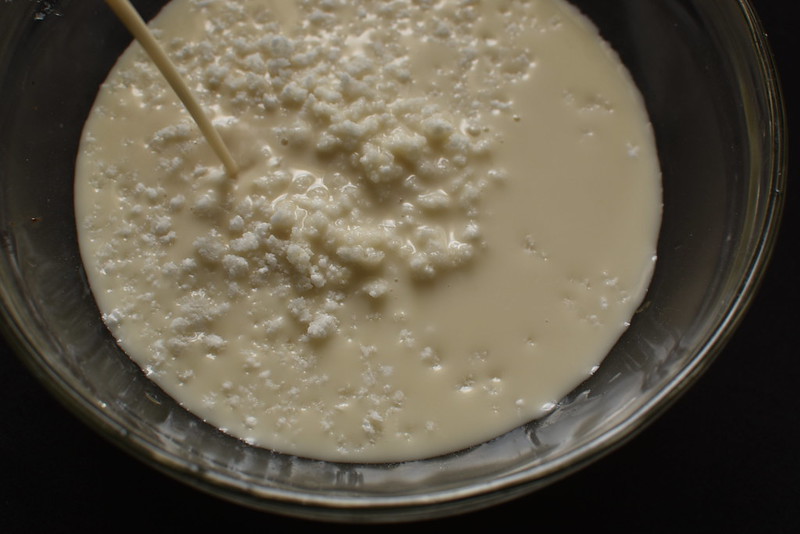

To cook, the granules are soaked in coconut milk or water until they soften and swell. The mixture is then slow cooked with lots more liquid and warming spices like cinnamon and cloves, stirring often to avoid clumping and cooking through, till the granules are soft and translucent. Tapioca loves liquid and continues to absorb it, thickening as it stands off the heat so lots of liquid is needed to avoid stodgy pudding.

It’s Easter season and the shelves of my local supermarket are sporting packets of Tapioca granules. On the streets of Lagos Island, you see them too, tied in transparent nylon bags ready for Easter feasts that will have frejon and kanjika on the menu.

Some stores – like L’Epicerie, a French shop in Victoria Island, owned by a Nigerian-French couple, have tapioca all year round.

This year, I decided to go down a few paths.

Path #1 – Using a tiger nut, coconut and date milk to cook it, rather than just coconut milk. This trio is considered an aphrodisiac by many, particularly in the north of Nigeria. It’s made it’s way down south and is beloved, and delicious.

Once my liquid gold was set, I proceeded to soak my tapioca in it for a few minutes, till all the liquid had been absorbed.

I like my mingau really liquid with the tapioca shining through and so I added more liquid till it was just so.

And then I refrigerated it. Weirdly, I like the taste and texture of reheated mingau – I feel as though the tapioca granules tighten and become firmer compared with straight off the fire.

The tapioca sets firm so I have to begin the process of loosening it up with more liquid when I reheat but I do not mind that one bit.

Path #2 – creating other desserts from it, like bruleed mingau. I had parfaits in mind but I didn’t quite make it.

Tips:

Creme brulee mingau: this version was cold set with sugar over the top which was then heated. The contrast between the slightly bitter, crunchy top and the creamy dessert was lovely. And there are so many ways to jazzz it up if you like with flavoured and spiced sugars

Warm mingau with pawpaw jam and orange zest – by far the favourite of my tester – the son. I like pawpaw and lime and would have gone for lime zest if I had limes at home. The oranges – the substitute worked so beautifully that I can only imagine how stunning the lime would be. And incredibly fragrant.

Forest Berry Mingau – Just some mixed berries over the top. This was lovely and refreshing. The tart berry juices worked well with the creamy mingau. So delicious.

Cinnamon mingau – a classic. Warming and fragrant, it was simple but nice.

Amoriri (Nigerian black plum syrup, Vitex Doniana) with toasted sesame seeds – one of my favourites because #NewNigerianKitchen and also peculiar, delicious flavours – rick, dark and intriguing.

Carrot cake jam with hibiscus – my taster didn’t like the idea of this from the get go so I guess its way at the bottom.

But, what a feast. A delightful, vibrant, tasty selection of toppings, fruits, jams, sauces and more to create a wealth of options this Good Friday.

What’s your favourite of the lot?

Leave a Reply